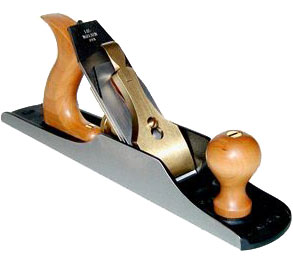

The Lie-Nielsen No. 102 is a low-angle bevel-up Block Plane, with the body available in Manganese Bronze. The bronze body will not rust. The blade is made from A2 Tool Steel hardened to Rockwell 60-62, which holds a sharp edge for a long time. The No. 102 is 5 ¼” long and the blade is 1 ¼” wide and 1/8” thick.

The Lie-Nielsen No. 102 is a low-angle bevel-up Block Plane, with the body available in Manganese Bronze. The bronze body will not rust. The blade is made from A2 Tool Steel hardened to Rockwell 60-62, which holds a sharp edge for a long time. The No. 102 is 5 ¼” long and the blade is 1 ¼” wide and 1/8” thick.

The size of this block plane is one inch shorter than Lie-Nielsen’s No. 60-1/2 Adjustable Mouth Block Plane, and is a perfect fit in my hand, which could account for at least one of the reasons I reach for it so often. The No. 102 is amazingly solid and works wonderfully. I enjoy the added heft of the Manganese Bronze, as

I’ve observed that heavier planes have a much greater tendency to run on what I might call autopilot. Obviously, adding extra weight to a plane presumes the design is nicely balanced, or the additional weight could easily be counter-productive, but that is certainly not an issue on the No. 102. The extra mass helps keep the plane moving through the cut, with seemingly less effort once you get it started on its path. On planes with as small of a body as the No. 102, the added weight from the Manganese Bronze will have less of an effect than on the larger frames, but it is still an added benefit.

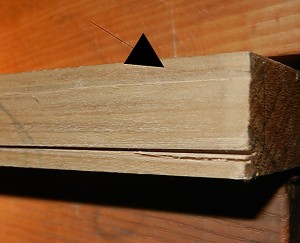

The low-angle Block Plane was originally designed for endgrain work, so it is no surprise that the Lie-Nielsen No. 102 is exceptional working on endgrain. To prevent accidentally chipping out or splintering the far edge of a board when working the endgrain, I always make sure to create a small chamfer on that edge. The chamfer is a very effective method to prevent these issues, without much work or loss of material. Start small, as you can always apply a bit more chamfer if you need to take more shavings, but it is hard to remove one that is too deep.

The small format of the No. 102 is also good for touching up a small isolated spot, even if the surface isn’t completely flat, as the length and width of the plane body can sometimes allow access that other planes could not reach. I even used my No. 102 on some of the outside curved edges on the Les Paul guitar I built, as some areas of those edges were endgrain, and also on the back side of the neck.

As with most bevel-up planes, the No. 102 has a great deal of flexibility relative to adjusting the cutting angle the wood will “see”. I’ll explain what I mean by providing a short example: The blade on the No. 102 comes from the Toolworks with a 25 degree bevel and is bedded at 12 degrees, which provides an effective cutting angle of 37 degrees. If you find the wood you’re working doesn’t respond well to this angle, you could apply a micro bevel from 1 degree all the way up to just shy of 53 degrees (since that added to the earlier 37 degrees would put it at 90 degrees), although I’d work my way up starting with a 10 degree microbevel and adding a slightly higher angle incrementally until I found the “sweet spot” for a specific wood. As info, this level of adjustment is not easily obtained on standard bench planes that have the blade’s bevel down. If you regularly transition between easier to work woods and woods that behave best with a higher cutting angle, it would make a great deal of sense to purchase a spare blade to leave with the higher microbevel, rather than repeatedly changing the angle from low to high and back.

There is also another replacement blade available, which is the Toothing Blade. This blade has small .030” teeth spaced .030” apart. This is very useful when working extremely figured wood that needs a decent amount removed. When dealing with wood of this type, it is extremely likely a regular blade will cause heavy tearout, if set to take even a somewhat heavy cut. With the Toothing Blade, the wood fibers aren’t allowed to work together against the blade, since each of the small teeth separate the sections from each other, ending with what looks like a lot of very small chips. The ending surface is very ridged and not at all like you might otherwise expect, but it is still very close to perfection. Reinstall a freshly sharpened regular blade and set for a very light shaving by using a thin piece of wood to verify the intended shaving thickness at each edge of the plane. Remember to trust your blade setting when you start to take passes over the toothed board, as it can seem like there is less happening initially, and a tendancy is to start advancing the blade. If you do that, you may end up overshooting and again have unintended tearout.

The Lie-Nielsen No. 102 is a great addition to any kit and I think you’ll find yourself using it perhaps even more than you might have anticipated. With the reasonable pricing for such a nice plane, you might want to get a second one for that friend that likes to borrow your tools, so yours will always be at hand.

I hope you enjoyed the article and please let me know if you have any questions or comments.

Lee Laird has enjoyed woodworking for over 20 years. He is retired from the U.S.P.S.

Ok, so lets talk about what you need to get started woodworking.

Ok, so lets talk about what you need to get started woodworking.