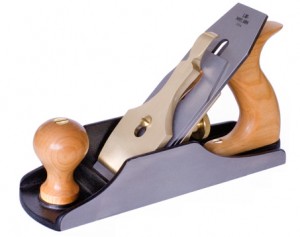

I remember when I first started woodworking and purchased some hand planes and chisels, no matter what I did, they never would work as I expected. I know many, if not most, woodworkers have had at least some period of time where they were less than happy with the results of their edged tools. One of the main reasons that mine initially didn’t work as expected nor as I’d seen in videos, was the fact that what I thought was sharp, wasn’t truly sharp at all. It’s funny how you can spend time on a sharpening stone (or insert just about any other method of sharpening here) and see polished surfaces, which I interpreted as “sharp”, but still make almost no progress. One of the missing puzzle pieces, for me, was when I finally got to try using a truly sharp plane iron and chisel. This completely opened my eyes as to whether or not my tools were sharp. NOPE! First thing that ran through my head was “So that’s what it feels like when it’s truly sharp”.

I remember when I first started woodworking and purchased some hand planes and chisels, no matter what I did, they never would work as I expected. I know many, if not most, woodworkers have had at least some period of time where they were less than happy with the results of their edged tools. One of the main reasons that mine initially didn’t work as expected nor as I’d seen in videos, was the fact that what I thought was sharp, wasn’t truly sharp at all. It’s funny how you can spend time on a sharpening stone (or insert just about any other method of sharpening here) and see polished surfaces, which I interpreted as “sharp”, but still make almost no progress. One of the missing puzzle pieces, for me, was when I finally got to try using a truly sharp plane iron and chisel. This completely opened my eyes as to whether or not my tools were sharp. NOPE! First thing that ran through my head was “So that’s what it feels like when it’s truly sharp”.

When I first started out I was trying all sorts of methods to get a sharp edge, from old carborundum stones (also known as a silicon carbide stone) and then on to some King water stones, scary sharp via sandpaper…The carborundum stone was slow removing material and the main reason I tried it was someone had left it in our garage when we bought the house. The King stones dished out so quick that soon all of my chisels and plane irons looked like they were smiling at me, since the surface shape of the stone is directly copied to the tool. I assumed I could just sharpen without needing to flatten the stone. What an eye opener. I had also watched master craftsmen sharpen their tools freehanded and I thought it would work for me, too. I remember looking at some of the bevels on both my plane irons and chisels, and you’d think I was practicing at being a gemologist or something with all of the facets I made.

Let me step back for a moment and provide a definition of sharp. It is the intersection of two highly honed surfaces, coming to a point with zero radius. As far as I know, the zero radius is an ideal, but the closer you can get to the ideal, the better. I know there are those of you out there that get great results sharpening all their tools freehand, and that is a really good skill to learn, but I normally will only freehand sharpen the tools that don’t work well in a honing guide. (Think corner chisels and other similar tools…)

I sharpen almost every tool in my shop with a micro bevel about 5 degrees stronger than the main bevel. This does a couple of things. One aspect is with the micro bevel’s higher angle, the edge is somewhat stronger and may resist breaking down as quickly as a weaker lower angled edge. Another is the fact that only the very tip of the cutting edge is sharpened, which makes it much faster than working to sharpen the whole primary bevel surface. This last aspect also makes it trickier to sharpen freehanded, since the micro bevel is so narrow, that I can’t “feel” it on the stone to know I’m registering the correct angle. I’ve found that for most sharpening needs, I have complete repeatability using an inexpensive honing guide like this one sold at Highland Woodworking, in conjunction with a free plan for building a sharpening jig available for download. I personally sharpen on a Norton combination 1000/8000 water stone. I put my tool into my honing guide and register the sharp edge against the wooden stop on the jig, with the bevel facing down, appropriate for the angle I’m working, and tighten the guide. Next I’ll make sure my stone is flat, for which I normally use an x-course diamond plate. You could easily do the same thing with sandpaper on a flat surface, but that is up to you. One method we use to verify the stone is flat, is to take a regular pencil and mark a grid across the length and width of the stone. When all of the pencil is removed by your diamond plate or sandpaper, the stone is flat. Now, I’m ready to sharpen the bevel side of the tool, starting on the 1000 grit side of the stone. Many of our show attendees ask how we know when we’ve sharpened enough on any one grit. I use my thumbnail, moving along the back of the iron towards the sharp edge (just be careful and never move across the sharp edge). When I feel the burr or wire edge across the full width of the tool, then I know I’ve sharpened all the way to the edge, which is what is needed. I’ll then move on to the 8000 side of my stone, repeating the same steps.

I sharpen almost every tool in my shop with a micro bevel about 5 degrees stronger than the main bevel. This does a couple of things. One aspect is with the micro bevel’s higher angle, the edge is somewhat stronger and may resist breaking down as quickly as a weaker lower angled edge. Another is the fact that only the very tip of the cutting edge is sharpened, which makes it much faster than working to sharpen the whole primary bevel surface. This last aspect also makes it trickier to sharpen freehanded, since the micro bevel is so narrow, that I can’t “feel” it on the stone to know I’m registering the correct angle. I’ve found that for most sharpening needs, I have complete repeatability using an inexpensive honing guide like this one sold at Highland Woodworking, in conjunction with a free plan for building a sharpening jig available for download. I personally sharpen on a Norton combination 1000/8000 water stone. I put my tool into my honing guide and register the sharp edge against the wooden stop on the jig, with the bevel facing down, appropriate for the angle I’m working, and tighten the guide. Next I’ll make sure my stone is flat, for which I normally use an x-course diamond plate. You could easily do the same thing with sandpaper on a flat surface, but that is up to you. One method we use to verify the stone is flat, is to take a regular pencil and mark a grid across the length and width of the stone. When all of the pencil is removed by your diamond plate or sandpaper, the stone is flat. Now, I’m ready to sharpen the bevel side of the tool, starting on the 1000 grit side of the stone. Many of our show attendees ask how we know when we’ve sharpened enough on any one grit. I use my thumbnail, moving along the back of the iron towards the sharp edge (just be careful and never move across the sharp edge). When I feel the burr or wire edge across the full width of the tool, then I know I’ve sharpened all the way to the edge, which is what is needed. I’ll then move on to the 8000 side of my stone, repeating the same steps.

The micro bevel will grow wider after honing multiple times, which can negate the time-savings of the micro bevel touch up. When this occurs, it is best to re-establish the primary bevel, so you can again utilize the micro bevel benefits. I reinitialize the primary bevel by placing sandpaper onto a flat surface like some thick float glass, some granite or the bed of a jointer. Use a second honing guide, so the grit isn’t transferred to your stones, and set the blade to the correct angle and work it back and forth until the original bevel is restored and the micro bevel is gone. Some prefer to utilize a grinder, but I like the strength of the flat primary bevel, compared to the slightly dished bevel caused by a grinder. Ultimately, this is a personal preference, so use whichever works best for you.

Now I’ve talked about sharpening one side of the iron/chisel, but as I mentioned in my definition of sharp, both sides must be highly honed. Without that, the lesser of the two will dictate the sharpness of the tool. I’m sure some of you out there are starting to cringe, at least those of you who have spent countless hours honing the backs of plane irons, to the point of a mirrored surface. Been there, done that! While this does fit the sharpening definition for the back, for plane irons it is unnecessary. We utilize a technique that David Charlesworth shared with us, called the ruler trick, that allows us to hone just the area nearest the cutting edge on the back, and still create a razor sharp tool. This does create the very smallest micro bevel on the back of the iron but is so small as to be negligible in function. (Do not use this technique on chisels, as you want to retain the ultimately flat reference surface. Just work the first half-inch or so of the back when honing.) In the ruler trick, a metal ruler with an extremely thin cross-section is placed on a prepared honing stone, along one of the long edges. The ruler is held in place by the surface tension created by the water applied during preparation. The plane iron is placed across the stone, so that the sharp edge is slightly hanging off the stone, while the remaining portion of the iron is across the stone resting on the ruler. If you were to put the sharp edge directly on the stone, the iron could easily gouge it. Now, keeping the iron flat against the stone and ruler, slide the sharp edge off and on (only about a 1/4” onto the stone) the stone repeatedly until the burr or wire edge is removed. This usually takes about 10 or so strokes, but test to make sure you are finished. When the burr or wire edge is gone, you should have a razor sharp tool.

With this method of sharpening, the beginner is immediately vaulted to a new level and will find their tools working as they were intended. They will also be able to quickly and reliably either refresh or initialize plane irons and chisels. Come out to see us at one of our shows if you still don’t feel comfortable sharpening, or if you’d like to try out some tools we’ve sharpened with this method. I hope to see some of you at our events across the country. Feel free to come up and say hello.

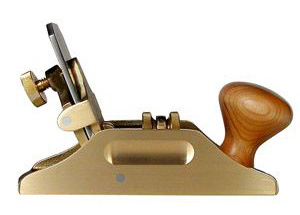

Lee Laird has enjoyed woodworking for over 20 years. He is retired from the U.S.P.S. and works for Lie-Nielsen Toolworks as a show staff member, demonstrating tools and training customers.

To watch a great demo video of the sharpening process, click here.

Check out the great selection in Highland Woodworking’s sharpening department.