Editor’s Note: A few years ago, a couple of well known woodworkers (The Wood Whisperer, Tom’s Workbench, Modern Woodworker’s Association, just to name a few) started woodworking safety week, which later turned into Woodworking Safety Day. This day is tomorrow, May 1st and we thought we would have some of our bloggers share their own woodworking safety stories and tips.

Over the last 20 years, I have worked in several different shops, from welding to woodworking. In each shop, I witnessed quite a few accidents, and in most cases, at least one of three things caused all. The number one cause of accidents that I witnessed was a messy shop. The worst accident I saw was my coworker got his feet tangled up in a rat’s nest of an extension cord while working at the table saw. Instead of paying attention to his hand placement he was paying attention to stepping around the extension cord and ran his hand right into the blade. Three surgeries later, he has partial use of his hand. Too bad SawStop wasn’t around back then.

It doesn’t stop with tripping over cords on the floor. The tangled extension cord can catch you off guard at the workbench as well. I have had the cord of a router tangled up on a pile of stuff on the workbench. While trying to hold the router with one hand and get the cord untangled with the other, I ruined my work piece. Luckily that is all I ruined.

Having a messy shop goes hand in hand with the second stooge of a dangerous shop, and that is being in a hurry. I don’t know how many times I have seen coworkers and I as well use the wrong tool for the job because we were in too much of a hurry to stop and go find the right tool. We run around the shop looking for that clamp to clamp down the work piece to the drill press only not to find it. We are in such a hurry to get back to work on the project we say, “Screw it” and decided just to hold the piece down, only to have it spin out of control when the drill bit catches. A flying work piece often results in smashed fingers, loss of fingernails, or worse yet, stitches. There are far worse examples of being in a hurry that can result in far worse injuries. Using the wrong tool for the job can be devastating. If we hadn’t been in such a hurry we would have cleaned the shop as we went, making it easier to find the right tool for the job.

The third stooge for a dangerous shop I have witnessed is complacency. I may not have seen this one as often as the messy shop or the hurried worker, but it often results in some of the most horrific injuries. It most commonly happens when doing product work, or a repetitive process. When I worked in a welding shop, we had a huge metal shear that would shear sheet metal up to 3/4” thick. My coworker had several hundred of the same pieces to cut out. As the day went on his mind started to wander and he became very comfortable with the operation. Not paying attention (being complacent), he got his finger in between the guard and the work piece. When the shear came down the work piece flipped up and smashed his finger between it and the guard. The pressure was so great it split his finger open and shattered the bone. I changed jobs shortly after that incident so I am not sure how his finger healed, but it reminded us all to pay attention, and stay focused on the task at hand.

These three stooges of danger are not the only dangers in the shop but when an effort is made to prevent them, we can avoid many injuries, save many work pieces from the scrap bin, and have bigger paychecks from not missing work.

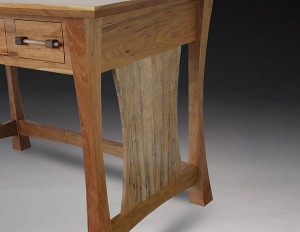

Brian Benham has made his lifelong passion for woodworking his profession. He enjoys taking his clients ideas and combining them with traditional woodworking techniques to create a unique piece of furniture.

You can find more about his furniture at http://www.benhamdesignconcepts.com/

You can Follow Brian on Google Plus